Digital photography has become second nature to most of us. Taking an image is so easy, so straightforward and immediate that we don’t think twice about it. When we see something noteworthy, we reflexively snap a couple of photos or shoot a short video. Then we put our device away, and often (if we’re being honest) never look at the images again.

It’s a similar story, in a way, with professional news imagery. Readers and consumers are so accustomed to seeing pin-sharp, high-resolution images from all around the world that they somewhat take for granted the immense technological achievements that have made this possible.

The journey that digital photography has been on is incredible – and well worth celebrating. So, we’re looking back at the history of digital image-making, from the first rudimentary images made on computers, to the present and future of digital photography. Here is the story of digital photography – how it started, how it evolved, and where it might be going…

1957 – The First Digital Image

Let’s go back to the middle of the 20th century. Photography – on film – is as popular as it has ever been, made incredibly accessible by affordable, portable 35mm SLR and rangefinder cameras. These find their way into the hands of newspeople and enthusiasts alike – and as far as most are concerned, they do everything photographers need them to.

All the same, some researchers have started to awaken to the possibilities that rapidly evolving digital technologies might have for image-making. In 1951, a team of Ampex Corporation researchers led by Charles Ginsberg invented a contraption that could take live images from a camera and store them as electrical impulses on magnetic tape. It would be sold in 1956, under the catchier and more familiar name of ‘video recorder’.

For the first thing we might think of as a digital photograph, however, we’d have to wait until 1957. At this point in the story, we meet one Russell Kirsch.

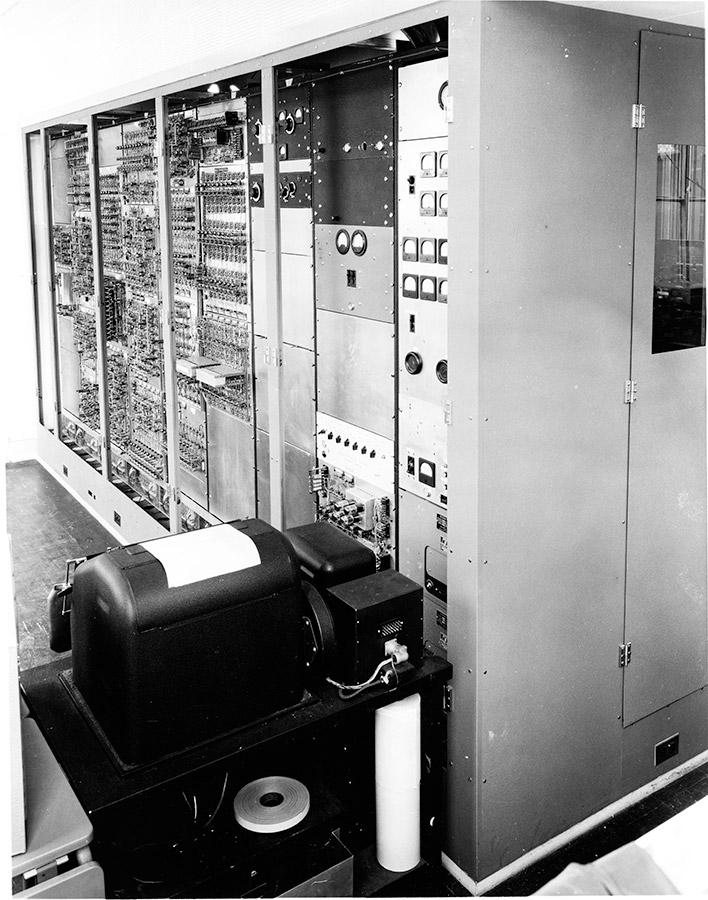

Kirsch was by all accounts a regular all-American guy. He worked a steady job at the National Bureau of Standards, and his wife Joan had a baby on the way. However, Kirsch wasn’t working just any job – he and his colleagues had in 1950 developed the USA’s first operational stored-program computer, known as the Standards Eastern Automatic Computer, or SEAC.

The Standards Eastern Automatic Computer that scanned the first digital image.

This computer would be used for all sorts of applications until its last run in 1964, from statistical analysis to meteorology. However, it was Russell Kirsch who first looked at the hulking machine – which back then was considered to be a relatively slimline computer – and had the thought, ‘Gee, y’know, we could probably load a picture into this thing.’

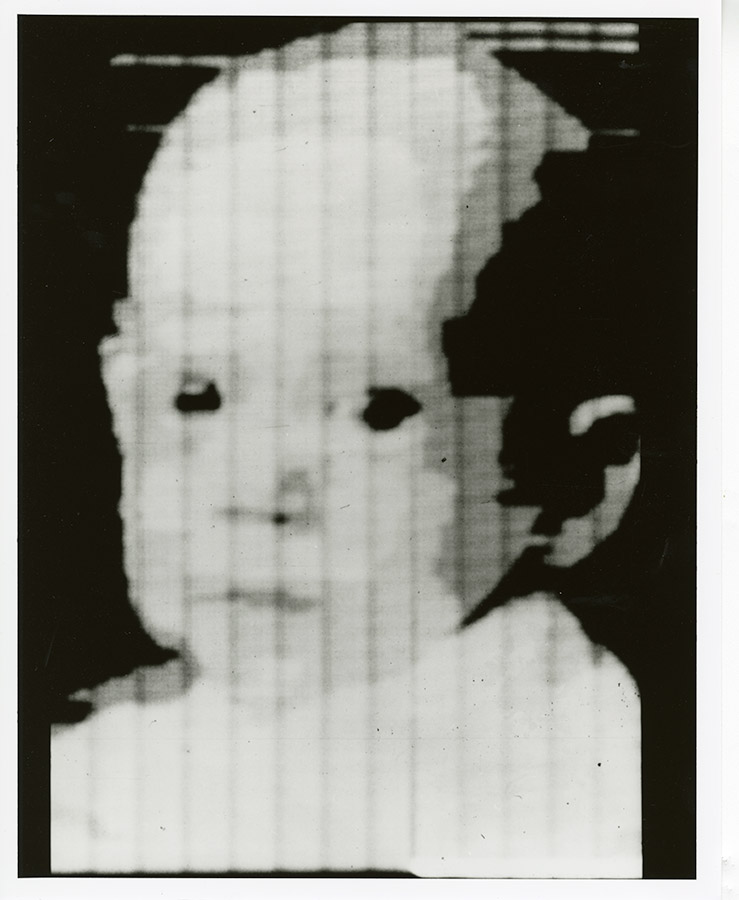

Kirsch and the team built their own drum scanner that would allow them to ‘trace variations of intensity over the surfaces of photographs’. With this, they were able to make the first digital scans. One of the first – possibly the very first – was an image of Russell Kirsch’s newborn son, Walden Kirsch.

The digitally scanned photograph of Walden Kirsch.

By modern standards, this image wasn’t much of anything. It measured just 173 pixels on each side and covered an area of 5x5cm. It had a bit depth of one bit per pixel – it could only classify pixels as black or white, so the team made the shades of grey by compositing several scans done at different intensity thresholds.

Despite its technical limitations, this image would take its place in history. All digital imaging – from security footage to press photography to Uncle Bob’s iPad photos of his niece’s wedding – would follow on from this picture of Walden. It would go on to be honoured by Life magazine in 2003 as one of the “100 photographs that changed the world” – which it most certainly did.

1960s – The Space Race

Kirsch’s image, while an inarguable technical milestone, wasn’t going to bother professional photographers much with its 173-pixel edges and rudimentary greyscale tones. Not while they had gorgeous 35mm colour film to work with.

However, digital imaging was beginning to garner interest in another quarter. Throughout the 1960s, the world’s superpowers were vying with each other to be the first to raise their flags beyond the Earth’s atmosphere, a competition that would become known as the Space Race. And, as everyone who’s been on holiday knows, you can’t really say you’ve been somewhere unless you’ve come back with some photos to prove it.

Film, for all its wonderful qualities, is not a practical medium for spaceflight images. So researchers started looking into other ways they could capture the great beyond. The USA’s Mariner 4 was set to make a flyby of Mars in 1965, and one of its goals was to capture the first photographs of the red planet.

Mariner 4, which captured the first photographs of Mars.

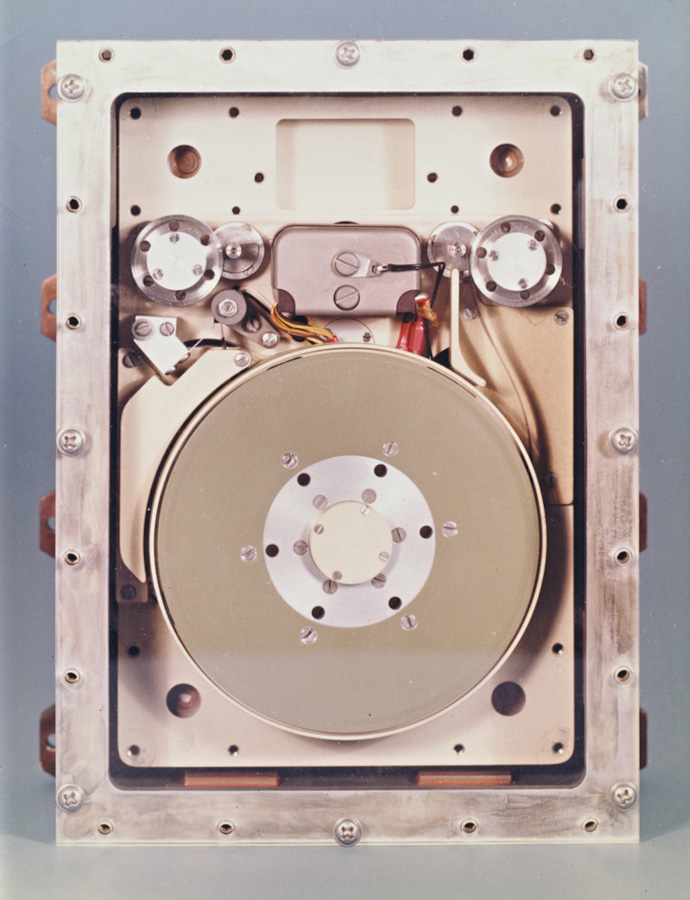

Taking cues from the work of Charles Ginsberg and his team at Ampex Corporation, NASA outfitted Mariner 4 with a magnetic tape recorder. It would use this to convert the image from its attached TV camera into electrical impulses that could be transmitted back to Earth via satellite, giving NASA its photograph of Mars.

The tape recorder on which Mariner 4 recorded its image data.

On July 15th, 1965, Mariner 4’s camera was switched on and it began to transmit photographs back to Mission Control. As the data started coming in, the team were at first concerned that something was technically wrong. This actually led them to get some pastels from a nearby art supply store and hand-colour the first photograph using the raw data in a paint-by-numbers fashion, to check the data they were getting was making sense.

The hand-coloured first image of Mars.

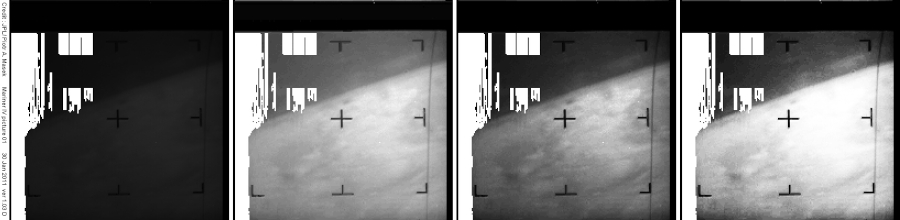

Happily, it was, and the rest of the images started to come in. Digital photography had found its first real use case – among the stars.

The images from Mars, at different stages of processing.

1969 – CCD Chips

The beating heart of a digital camera is its sensor. Fulfilling the same function as a frame of film, a sensor records the light that hits it, and sends it to the processor for the necessary translation that makes it a digital image.

At this point in the digital photography story, sensors start to enter the picture. In 1969, Willard Boyle and George Smith of Bell Labs developed something they called a charge-coupled device, which digital photographers with long memories might find more familiar if we refer to it by its more common name – a CCD. Essentially, it used a row of tiny metal-oxide-semiconductor (MOS) capacitors to store information as electrical charges (fulfilling the same function as the magnetic tape in the older cameras).

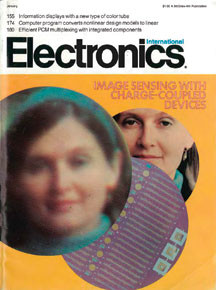

Though Boyle and Smith were mostly concerned with computing, subsequent inventors made the connection that if you were to pair this device with something photosensitive, you’ve got yourself a rudimentary camera sensor. In 1972, the first published digital colour photograph splashed on the front of Electronics magazine, taken by British-born engineer Dr Michael Tompsett, and placed side by side with a (much clearer) film photograph for comparison. In a touch that hearkened back to Russell and Walden Kirsch, the photograph was of Dr Tompsett’s wife, Margaret.

Margaret Tompsett on the cover of Electronics. The digital image is on the left.

CCD would remain the dominant form of digital image sensor until the CMOS sensors that are near-ubiquitous on cameras today would start to edge it out in the 2000s. With CCD technology, digital photography was going from a niche curio to something that image-makers and tech heads could justifiably start getting excited about.

1970s and 1980s – The First True Digital Camera

What was the first real digital camera? There’s actually more argument about this than you might think, the short answer being: it depends on how you look at it.

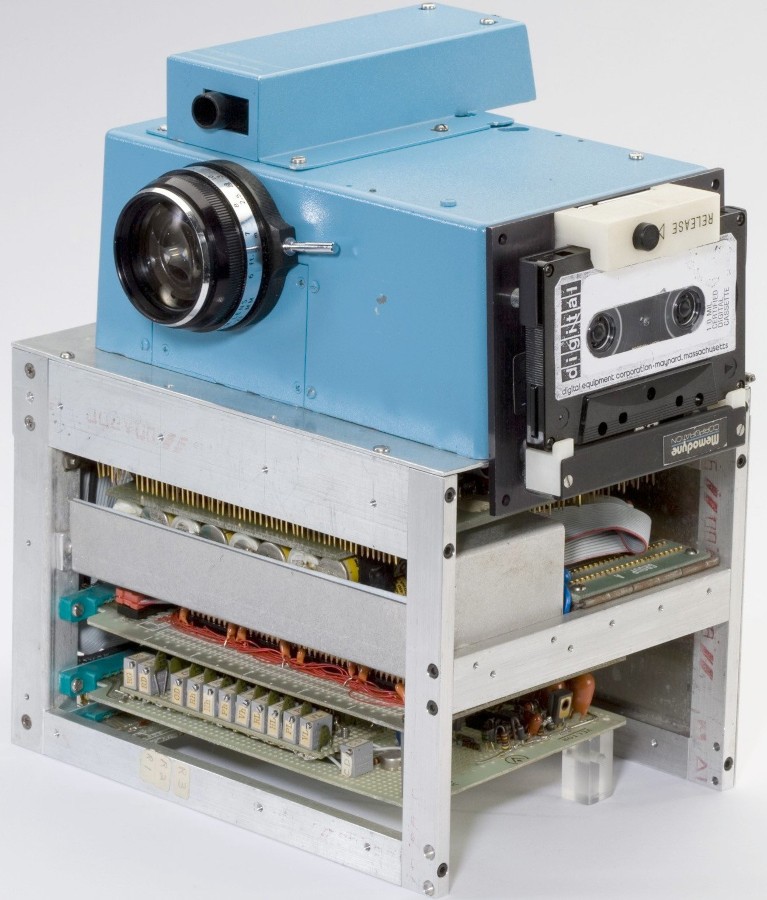

If you ask the question of a camera history buff, it’s likely they’ll point you towards the digital still camera developed by Eastman Kodak engineer Steven Sasson, in the year 1975. Sasson, in his twenties, had just bagged a job at Kodak. His superiors gave him a non-priority, busywork task to keep him occupied, telling him to see if anything interesting could be done with any of those new-fangled CCD imaging sensors.

‘Hardly anybody knew I was working on this, because it wasn’t that big of a project,’ Sasson would later recall to the New York Times’ Lens Blog. ‘It wasn’t secret. It was just a project to keep me from getting into trouble doing something else, I guess.’

Sasson took a few of the most recent CCD electronic sensors and crammed them into a bizarre Frankenstein’s monster of a device – using, among other things, a lens taken from an old Super 8 movie camera. The result looked somewhat like an overhead projector stacked on top of a toaster, but here’s the thing – it worked. It recorded black-and-white images to cassette tape, with a resolution of just 0.01MP.

Steven Sasson’s original digital camera prototype. Image credit: George Eastman House.

Of course, Sasson’s camera was just an experimental prototype. No version of it ever got close to a point where anyone could walk into a shop and buy it. That’s why Sony also claims to have produced the first true digital camera, as in August of 1981, the manufacturer debuted its own prototype.

The prototype Sony Mavica from 1981, photographed in 2011. Image credit: Morio/Wikimedia Commons.

The Sony Mavica, which looked a lot like a contemporary SLR, used CCD chips to record images onto a 2x2-inch floppy disk that could hold around 25 frames. It was referred to as the world's first electronic still video camera, as that’s pretty much what it was – a video camera that recorded still frames. As such, the quality of the images it produced was comparable to that of televisions at the time.

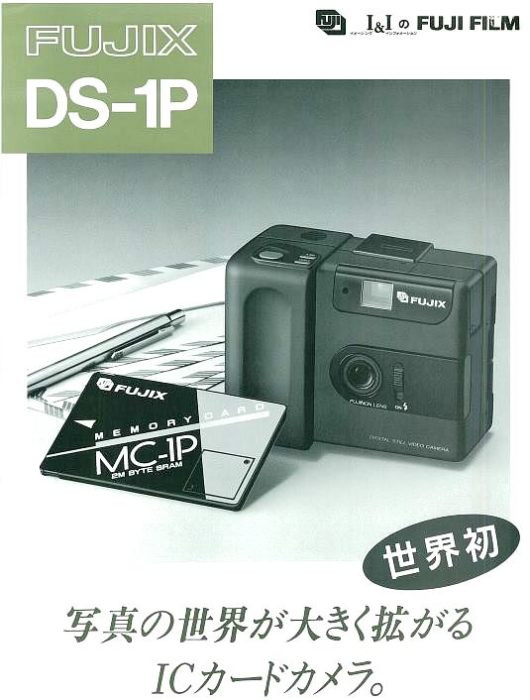

Now, eagle-eyed readers may have noticed that these digital cameras still had decidedly analogue elements, such as the magnetic tape used to actually store the images. That is why Fujifilm also claims to have produced the world’s first ‘true’ digital camera.

Debuting in 1988, the FUJIX DS-1P used a CCD sensor just like the cameras that had come before it, but it was the first one to store its images on a semiconductor memory, rather than on tape. This meant the entire process, top to bottom, was fully digital. While the DS-1P was just a prototype, it would be followed a year later by the commercially available FUJIX DS-X.

A poster showing off the DS-1P and its memory card. Image credit: Fujifilm.

Who made the first true digital camera? Was it Steven Sasson at Kodak? Sony? Fujifilm? Some of the many other legitimate claimants we haven’t had space to mention? You’ll have to make up your own mind on that one, because in our timeline, a big player is about to enter the picture.

It’s time for us to meet the DSLR.

1986 – The Age of the DSLR Begins

It was always inevitable. From the moment those CCD image sensors were invented, it was only a matter of time before someone would think to start putting them in the SLR-style body, with ergonomics that had been honed for decades.

Nikon was first out of the gate. In 1986, the firm took the wraps off of a prototype of the world’s first digital single-lens reflex camera – the Nikon SVC (or Still Video Camera). If we’re being picky, we could point out that it was actually manufactured by Panasonic, but nevertheless, the SVC had Nikon branding all over it. Built around a 2/3-inch CCD sensor with 300,000 pixels of resolution, it stored images on an internal magnetic floppy.

While the SVC was a prototype, it was swiftly followed by the commercially available Nikon QV-1000C, released in 1988.

The Nikon QVC-1000C at the Nikon Museum. Image credit: Morio/Wikimedia Commons.

The DSLR was well and truly on the rise – and it was about to be helped along by a few concurrent technological developments that suddenly made digital formats a lot more viable.

As we’ve seen, storage was a bit of a thorny issue on early digital cameras. Taking the images was all well and good, but where were you supposed to keep them? Digital storage was in its early days, and bodge-job solutions like the magnetic tape were less than ideal. Many digital cameras could take a maximum of 25-50 images before they needed to be offloaded (a much more complex process in the days before portable card readers and Wi-Fi). This severely curtailed their usefulness as professional tools.

A committee known as the Joint Photographic Experts Group was doing some interesting research quite separate from cameras and lenses. They were focused on the actual digital image file, and developing new coding methods that could allow these files to be stored much more efficiently than they had been before, with little to no loss in quality. The group finished their research in the late 1980s, and the new image compression standard was officially released in 1992.

It’s hard to understate the extent to which this changed the game – suddenly, digital cameras were real, viable tools for working photographers. Even if the quality wasn’t on par with film (yet), the efficiency and agility of the format had many advantages of its own – no more dangerous chemicals, no more cumbersome darkrooms. And if you’re wondering why you’ve never heard of the Joint Photographic Experts Group, given that they did so much for digital photography, then the answer is likely because you know them by another name…

The logo for the Joint Photographic Experts Group.

1990s – DSLRs Dominate

The 1990s was something of a gold rush for digital photography. Camera after camera came tumbling onto the market, with dazzling new technological firsts arriving every year. In 1990, the Dycam Model 1 or Logitech Fotoman arrived, with the ability to connect to a computer in order to offload its images. In 1995, Casio brought out a camera called the QV-10, which had a new-fangled gadget called a ‘liquid crystal display’ on its rear that allowed the user to view playback of their images – though the name would later get shortened to LCD. Ricoh’s RDC-1, also in 1995, was one of the first ‘multimedia’ cameras to offer both stills and video recording.

In 1996, Kodak introduced the DC-25, which offered compatibility with a fast, high-capacity new memory card format called CompactFlash. Indeed, it sounds odd today given how things ultimately shook out, but Kodak was the dominant name in professional digital photography for much of the 1990s. Remember, Steve Sasson had been working for Kodak when he’d made his prototype. Many of the major names in film photography – Canon, Nikon – made an ungainly transition to digital by slapping their own branding on a Kodak-made body.

As the decade went on, camera manufacturers started to make the canny realisation that they’d have an easier time tempting older photographers onto the new digital systems if they let them bring their lenses along too. Accordingly, Minolta brought out the RD-175, based on the Minolta 500si film SLR, but packed with three independent CCD sensors. Most importantly, it could take Minolta AF-mount lenses.

The Minolta RD-175 was a chunky boy. Image credit: Rama/Wikimedia Commons.

However, it was Nikon that really nailed it in 1999, with the introduction of the Nikon D1. Breaking free from its partnership with Kodak, this was an all-Nikon camera from the ground up. It resembled the Nikon F5 in looks, feel and handling, which is no bad thing to resemble. This meant that Nikon film shooters, of which there were still a lot, could very easily jump onto the D1 and learn how to use it, and they could bring all their old F-mount lenses with them.

The D1 also had a number of other things going for it, such as fast autofocus, and a clever CCD sensor that essentially oversampled its photosites to create 2.7MP images of excellent clarity and sharpness.

There were some missteps – the Nikon D1 used the NTSC colour space rather than the more popular sRGB/AdobeRGB colour spaces, resulting in some images with odd-looking colours. But the Nikon D1 was a resounding success – it spelled the beginning of the end for Kodak’s dominance in the professional photography space, and essentially signified the true beginning of the digital era. The line would continue for more than twenty years, culminating with the release of the Nikon D6 in 2020.

The Nikon D1, a pioneering professional DSLR. Image credit: Ashley Pomeroy

A year later, Canon would bring out the D30, its first DSLR entirely made in-house – another break from dependence on Kodak. It was the smallest, lightest DSLR on the market, and boasted class-leading autofocus thanks to its adoption of a new type of sensor – the CMOS, which had been originally developed by NASA.

DSLRs and other digital cameras would explode in popularity throughout the 2000s. The product lines began to split and diversify. Full-frame DSLRs – i.e. with sensors the same size as a frame of 35mm film – began to appear, including the Pentax MZ-D, the Contax N Digital and the Canon EOS-1Ds. Compact cameras with fixed lenses became incredibly small and affordable. Rugged, SLR-style compact cameras with big zoom lenses attempted to bridge the gap between the two – and would become known as ‘bridge’ cameras.

Consumer digital cameras were the gadget of the moment – and they were about to explode in an unexpected new direction.

2008 – The DSLR goes to Hollywood

No one really saw this coming, not even Canon. In 2008, the manufacturer released the EOS 5D Mark II, a professional-grade full-frame DSLR, which was notable for being the first full-frame DSLR to shoot video in Full HD (with a resolution of 1920x1080 pixels). Many of the photographers who picked up the camera probably didn’t even notice this, but the Canon EOS 5D Mark II had quietly been equipped with a seriously impressive video spec.

The Canon EOS 5D Mark II. Image credit: Charles Lanteigne

For starters, it used a 16:9 aspect ratio portion of the sensor to record video, creating a cinematic look. It could create a very shallow depth of field with large-aperture lenses, which opened up all sorts of interesting filmmaking possibilities. The large sensor meant it would do well in low light, and while it could only shoot at 30p on release, Canon would subsequently release firmware that allowed it to shoot at 25p and 24p, the latter of which is the standard frame rate used on movie productions. This meant that shots captured on the 5D Mark II could blend seamlessly with shots captured on motion picture film cameras.

Other firmware updates added more useful video features, and filmmakers began to notice that the EOS 5D Mark II was not only versatile and agile, but it was also a good deal cheaper than many of the cameras they were using. The result came to be known as the ‘DSLR Revolution’. The EOS 5D Mark II started being used for BBC sports coverage, including Grand Prix Snooker. It became pretty much the de facto camera of choice for independent filmmaking, and was used on big TV dramas such as House M.D. Shots taken on the EOS 5D Mark II even appeared in the biggest film of 2012 – Marvel’s Avengers Assemble.

The director of photography on Avengers Assemble, Seamus McGarvey, credited the EOS 5D Mark II for some of the shots in the finished film. Image credit: Marvel Studios

The Canon EOS 5D Mark II changed the way people thought about filmmaking. Today, you can buy one used for less than £400.

So, as we come to the end of the 2000s, it seems like the DSLR is king in both photo and video. However, two key challengers are already appearing on the horizon…

2010s – Mirrorless Rising

SLRs, and by extension DSLRs, are an incredible piece of engineering. The number of moving parts that have to work together in concert for the shutter-flipping mirror mechanism to work seamlessly and result in a correctly exposed image is nothing short of astonishing. All the same, with digital devices getting smaller and smaller, it’s hardly surprising that technically-minded people started looking at DSLRs and wondering if there was a way they could make these things a little smaller.

First, manufacturers looked at rangefinders for inspiration. These are cameras equipped with range-finding focusing mechanisms that use a different lens to the imaging one – Leica was most famous for them throughout the 20th century, and still makes them today. The first digital rangefinder to hit the market was the Epson R-D1, which felt so analogue that it even had a manually winding shutter.

It was swiftly followed by a digital rangefinder from the grandaddies themselves – the Leica M8 in 2006. It lagged a little behind times, using a Kodak-developed sensor, and this led to a few problems on release, including complaints of sub-par image quality. It would take Leica a few years to really hit its digital stride.

The Leica M8 was not without its problems. Image credit: Rama/Wikimedia Commons

But these weren’t mirrorless cameras. The first true mirrorless camera to reach the commercial market was the Panasonic Lumix DMC-G1. The manufacturers at Panasonic had made the clever realisation that those fancy liquid crystal displays could be put to use to provide a live image preview, eliminating the need for the mirror mechanism altogether. In fact, a tiny version of an LCD could even be used to approximate the experience of a viewfinder. And this is exactly what they did.

The Panasonic Lumix DMC-G1. Image credit: Rama/Wikimedia Commons

The G1 used the Micro Four Thirds sensor and lens mount standard – a smaller sensor size that allowed for lighter bodies than full-frame and APS-C. Panasonic unveiled this standard in partnership with Olympus, who would soon release its own PEN E-P1, which could interchangeably use the same lenses as the G1. This flexible, interconnected system proved so successful that it is still popular today.

Even so, it took mirrorless cameras a while to find their identity. Those electronic viewfinders were nifty in theory, but irritating in practice – they were too small, the resolution was too low to see any detail, and they lagged unacceptably behind the action. They couldn’t compete with a large, bright, immediate optical viewfinder.

As such, mirrorless cameras – or compact system cameras, as they were also known – often seemed to be marketed with an air of apology for not being DSLRs. Panasonic experimented for a while with calling its cameras ‘DSLMs’ (digital single-lens mirrorless), which didn’t really take. Sony, who had been producing a range of SLR-like mirrorless(ish) cameras using the Minolta A-mount for lenses, tried calling them ‘SLTs’ (single-lens translucent). Which… yeah. You get it.

But here’s the thing about technology – it gets better. The viewfinders started to improve. They got bigger, sharper, and faster. They started to be able to do things that optical viewfinders couldn’t, like display settings information in a useful readout. Other mirrorless systems started to arrive. There was Samsung NX, Pentax Q, and Nikon 1. Fujifilm revitalised the fortunes of its brand with the retro-style X-system of compacts and mirrorless cameras, debuting the brilliant X-Pro1 in 2012. Canon began a whole new mirrorless system with the APS-C EOS M-system. Then, something happened that kicked mirrorless into the big leagues.

In 2013, Sony took the wraps off the A7 and the A7R. These were full-frame, professional-grade mirrorless cameras, using Sony’s proprietary E-mount lenses. They marked the beginning of a whole new chapter in Sony’s history – they were smaller than DSLRs, but had electronic viewfinders that could keep up with the action.

They were soon joined by a third camera, the A7S, and now the A7 trio really had its identity. The A7 was the pro-grade all-rounder, good in all situations. The A7R was the resolution specialist, excellent for capturing high levels of detail. And the A7S? Well, the A7S was an absolute monster at shooting in low light, able to hit an ISO ceiling of 409,600, and effectively turn night into day.

The original Alpha 7 family. Image credit: Henry Söderlund

Somewhat like Canon did with the EOS 5D Mark II, Sony had made a landmark professional video camera practically without realising it. Filmmakers noticed how useful the portable A7S and its low megapixel count (12.2MP) could be for them, opening up shooting opportunities in low light. When it came time to revitalise the line with the Mark II versions, Sony released an A7S II that was a lot more tailored towards video.

As more and more photographers and videographers started to jump ship, camera manufacturers realised that high-end mirrorless was the future for professionals. As such, other full-frame mirrorless lines arrived – Nikon Z and Canon EOS R both debuted in 2018.

Panasonic, once again showing off its spirit of cooperation, would announce the formation of the L-mount alliance in 2019, joined with Leica and Sigma, and a new line of Lumix S full-frame mirrorless cameras.

These too would prove popular among filmmakers – comedian Bo Burnham produced the entirety of his smash-hit self-shot 2021 comedy special Inside on the Panasonic Lumix S1H.

Bo Burnham with his Lumix S1H. Image credit: Netflix.

In 2020, Canon released the EOS-1D X Mark III, and Nikon released the D6. These were both phenomenal DSLRs, and also very likely the last professional DSLRs that either firm would produce. The future of pro-grade cameras was, and is, mirrorless.

And meanwhile, at the other end of the user spectrum, a very different kind of imaging revolution was taking place.

Meanwhile, in the 2010s – Everyone Has a Camera Now

Steve Jobs and Apple did not invent the camera phone, no matter how many people think they did. People had been putting cameras on mobile phones as early as 1999, and had been figuring out ways to share images via mobile phones even before that.

In 1997, while waiting in the hospital for the birth of his daughter, French entrepreneur Philippe Kahn figured out a way to connect his camera, laptop and phone in order to be able to share a picture with 2,000 people all at once. When his daughter was born, he perhaps unwittingly paid tribute to Russell Kirsch and shared an image of his new baby that was simultaneously a world’s first – in this case, the first photograph shared via a mobile phone.

The tiny photograph in question. Image credit: Philippe Kahn

So, no, Steve Jobs didn’t invent it. However, the slim and attractive iPhone arguably paved the way for the notion of a camera phone as something everyone could, should and would own. Before, they had been thought of as unusual little gadgets for tech heads. Now they were slim, attractive, easy-to-use, and desirable. As smartphones grew in ubiquity, so did the smartphone camera. Suddenly, everyone had a camera within reach, at all times.

As other ranges of smartphones from the likes of Samsung and Sony grew in popularity too, digital photography had officially become thoroughly democratised. Now, everyone was a photographer, in a way that Russell Kirsch, Dr Michael Tompsett, Steven Sasson and all the other pioneers could scarcely have dreamed of.

2020s – The Age of Intelligent Imaging (The Infiltration of AI)

Where do we go from here? As sensor resolutions get higher, autofocus systems get faster, and processors get smarter, it’s hard to know what the future of digital photography will look like. At the start of the 2020s, the big buzzword was ‘deep learning’ - the use of AI to create systems that get better as you use them. By 2022, Canon had already implemented neural-learning autofocus systems in its cameras.

While there's plenty we haven't covered, including the rise of Photoshop and image editing, RAW format, GoPros and action cameras. Drones, 360-degree video, and even the resurgence of analogue film photography, at this point in history, the defining narrative focuses on intelligent imaging.

Come 2025, the mention of AI now conjures a myriad of thoughts and feelings, but the advancements in camera technology are generally considered to be positive. Autofocus systems like Canon’s Dual Pixel AF with deep learning or Sony’s real-time subject tracking (powered by its Bionz XR processor) can lock onto subjects with ease and precision - and not just faces, but eyes, animals, vehicles, even aircraft. And, these systems learn as you shoot, which has been an incredible step forward for fast-paced scenes like wildlife or sports.

Sony’s real-time eye-tracking. Credit: Sony

In fact, with the latter, cameras like the Canon R5 II and R1 have deep learning so advanced that you can set up to 10 faces in-camera for it to recognise, and then prioritise them from 1 to 10. This means when you’re on the field or pitch, the camera is able to pick out those specific faces among the rest. Not only this, but when we were testing the R1 on a basketball court (see here), the camera could tell we were on a basketball court and knew that players can suddenly appear and disappear from the frame and adjust accordingly, in an instant. It’s hard to think where in-camera technology will go next…

The Canon R5 II in all its glory. Credit: Wex (from our video review)

But while in-camera AI developments like advanced autofocus and subject tracking are largely celebrated, since 2022, the role of AI in editing and image production has sparked a more contentious debate. Briefly touching on this subject, the developments here directly affect the history and future of digital camera photography, as they bring into question the authenticity of photography. From AI-generated images taking ‘inspiration’ from celebrated works they were intentionally trained on, to hefty photomanipulation, it results in a world where you’re never quite sure if the images you see are real.

Much of the photography world seemingly thinks that we never asked for this when the likes of Adobe and Meta are pushing AI onto us without thought of the effect on digital camera photography. Even more concerningly, in early 2024, court documents revealed that the work of thousands of photographers and other artists had been used to train the AI image generator Midjourney.

What do the next few years of digital camera innovation look like? Because, at the pace we’re going, with artificial intelligence and deep learning firmly embedded in pre- and post-production of photography, we’re not just entering the age of intelligent imaging, we are already living in it.

FAQs

What is a digital photograph?

A series of individual digital pixels that each contain different colour values, combined together to form an image. Digital photographs are often referred to in terms of megapixels (or MP) – this means the number of pixels that make up the image. The more pixels you have, the more detailed the image is.

How do digital cameras work?

A digital camera’s sensor is covered in an array of millions of tiny light-sensitive areas called ‘photosites’. When the camera’s shutter opens, these sites collect the light they are exposed to, and store it as an electrical signal. When the shutter closes again, the camera asses how much light hit each individual photosite by measuring the strength of the electrical signal. Colour filter arrays placed over the arrays allow the camera to discern colours by only permitting light of a certain primary colour to hit a certain photosite.

Which digital camera is the best?

There’s no short answer to this! All digital cameras have their own strengths and weaknesses. If you’re looking for advice, we have a useful series of buying guides where we compare the strengths and weaknesses of different models.

I’m confused about a digital photography technical term?

That’s fair enough – there are a lot of confusing names, terms and acronyms associated with digital photography. Fortunately, we have a handy indexed jargon-busting A-Z of Photographic Terms on the blog, so check that out if you’re feeling lost.

About the Author

Jon Stapley is a professional journalist with a wealth of experience in a number of photography titles including Amateur Photographer, Digital Camera World and What Digital Camera.

Sign up for our newsletter today!

- Subscribe for exclusive discounts and special offers

- Receive our monthly content roundups

- Get the latest news and know-how from our experts