Together with his camera, Matt Emmett visits the places of our past to document what we leave behind. He tells us more about Forgotten Heritage

Abandoned attic. All images by Matt Emmett

Forgotten Heritage, Matt Emmett’s ongoing photography project, could be mistaken at a glance for the end of the world.

His images show stark, ruined buildings, overgrown and abandoned, littered with objects that reveal the life they once had. They are the places left behind when people move on, succumbing to decay and neglect. The ephemeral nature of his subjects – spin through the gallery and you’ll see many buildings that no longer exist – reminds us of how temporary the things we take for granted can be.

Ahead of Matt’s talk at our London Lens Show, we caught up with him to find out more about what it’s like to document the forgotten detritus of our recent past…

Farm kitchen

Wex Photographic: Thanks for talking to us, Matt. How would you describe the images that you create?

Matt Emmett: The poetic answer – buildings to me are a little like people. They have a character and personality all of their own, like an elderly person inhabiting a quiet and lonely place that is far removed from the hustle and bustle of their previous existence.

My images provide an intimate glimpse into the final weeks or months of a building’s life. Many of the buildings I photograph have played influential roles within a particular industry, or occupied a place in history. I consider capturing these images to be a huge privilege.

The technical answer – I try and keep the look of the images I create as close as I can to the scene I saw with my own two eyes. People often comment that my processing style has a very real feel to it.

WP: Which came first for you, Matt, the love of the abandoned locations you visit or photography?

ME: Photography. I started with a Pentax ME Super back in 1990 when I did the first of several long trips to South East Asia and India. I have only been shooting abandoned places and buildings at risk since 2012.

WP: What is it about capturing these hidden spaces that you enjoy the most?

ME: Just being inside a vast power station in total silence and stillness is a real treat. There is a unique and magical atmosphere that’s not found in locations that are still being used.

I have travelled to several of the world’s top UNESCO World Heritage sites, and as fantastic as they are, you are still sharing the location with hundreds or thousands of other people. Given the choice, I would much rather spend the day in an abandoned place.

Tool-makers' factory

WP: How do you go about researching the sites that you intend to visit?

ME: In the first instance, most of the location info comes via other photographers, but I have a growing file at home of places I want to visit, some of which I have been working on gaining legal access to for some time.

Once you know the name and location of a place, then finding out more is often just down to a simple web search. The fact that most photographers do not use the correct name when posting images online means getting the name and the address can be the hardest part.

WP: Do you ever find the negative stigma that’s sometimes associated with urban explorers to pose a challenge in your work?

ME: It has gotten worse over the last few years. In a short time, the hobby has gone from a small niche in a dark corner of the photography world to something that has exploded into the mainstream.

It was obvious that something so fascinating and exciting would capture people’s imaginations. Through the posting of the images on popular social channels and the media picking up on it, it was inevitable that it would attract people who would not treat the locations with the respect they deserve.

I tend not to use the term any more, and certainly not when I approach clients for access to an interesting location.

Portico

WP: How do you ensure that you stay on the right side of the law during your shoots?

ME: We don't damage, break, smash or cut anything to gain entry to an abandoned building, and we have walked away many times after determining access would not be possible without doing so. We never remove anything or take a keepsake with us.

Making sure you follow certain rules means you can't be criminally prosecuted. Avoiding access at certain location types is also a must – places like partially active military sites, power stations or royal properties.

WP: What’s been your favourite location to visit so far?

ME: Either a huge ex-MOD jet-engine-testing establishment (that no longer exists) or a large and stunningly beautiful abandoned asylum in northern Italy.

WP: You’ve visited quite a few Italian locations. How did these differ from those in the UK?

ME: Buildings in different countries all look architecturally different and exotic compared to what you are used to. Add to that the crumbling stone work and fading frescoes found in the villas and hospital across Italy, and for me it's a magical combination.

Asylum admin block

WP: Are there any other places around the world that you’d particularly like to go?

ME: Lots and lots. A few spring to mind. There’s the abandoned town of Pyramiden on Svarlbad, or the town of Anlong Veng in Cambodia, which is the last jungle stronghold of the Khmer Rouge. Also the subterranean Titan 1 ICBM nuclear launch bunkers across parts of the US. The list goes on and on.

WP: You must discover all sorts of unusual things in some of these forgotten buildings. What’s the strangest thing that you’ve stumbled across?

ME: I know of a US photographer who found a small fortune in currency tucked away inside a dresser in an abandoned house. He handed it all in to authorities, who then traced the relatives of the previous owner.

In an abandoned manor house, I found a chest full of amazing letters written by the head of the house, organising the master’s golf outings, thanking people for charitable donations and liaising with companies looking to deliver to the kitchens. There are always lots of interesting clues to be found that help reveal more about a place’s past.

WP: How has your work exploring these structures affected your view on their conservation?

ME: Many places I have photographed no longer exist. Some were important historical sites, and no plans were made for preservation of any kind before they were demolished. This brings home to me current attitudes to heritage by the government and the importance that photography can play in the act of preservation.

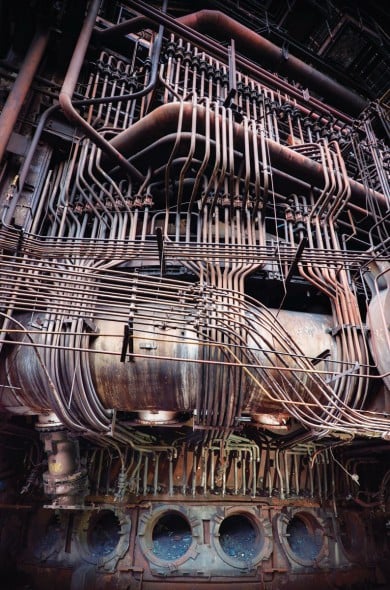

Blast furnace

WP: What equipment are you currently using to capture your images?

ME: Pentax K1, Pentax K3 II, Pentax KP, Pentax 645Z and a Canon EOS 7D that’s been IR-converted. I love the awesome image quality of the Pentax lenses and the ergonomics and feel of the Pentax bodies, as well as their strong, robust, weather-sealed construction. It is without doubt some of the best gear around for the kinds of locations I shoot in.

WP: How do you deal with what I imagine must often be tricky lighting conditions?

ME: I mostly process from either a single RAW or a set of three brackets. Due to the gloomy conditions present in these locations, and the limitations present in cameras regarding dynamic range I often have to produce brackets and blend parts of three exposures together to retain a good range in the final shot.

If the location is very dark then I bring out my portable Scurion lamps – I love light-painting in the details of an underground tunnel or reservoir. One of my light-painting images won me the Arcaid Images Architectural Photography Award 2016.

WP: What advice would you give to anyone inspired by your work to go and explore some forgotten spaces themselves?

ME: Don't do it alone, don't take big risks, follow the rules on respecting the location. Be polite if asked to leave. And have fun, because it really is a lot of fun!

About the Photographer

Matt Emmett is a photographer specialising in exploring and documenting derelict buildings. His website is forgottenheritage.co.uk, and you can follow him on Facebook